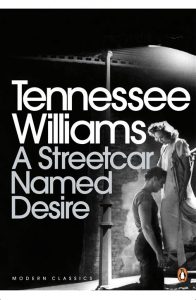

Following a short play, A Streetcar Named Desire, I thought I could dare a longer read… I have always been a fan of Steinbeck; I probably favour his and Anton Checkov’s works the most of all the books I’ve read.

I have read a number of Steinbeck books. Cannery Row was very memorable to me the first time I read it and quickly became a favourite of mine. A while later I discovered Fat Thursday, then Of Mice and Men. I also watched East of Eden, the classic with James Dean, a few times in my time.

However, I have not had the pleasure of reading The Grapes of Wrath.

I had heard of the work, I knew it was of his best, but I was still so impressed by the book when I read it.

The book takes place during the times of the Oklahoma Dust Storms, a period I was not that familiar with. It describes the adventure of the Joad family, a family of Oklahoma farmers, that struggle to make a living and survive in a time of depression, drought, and economic hardship.

The Joads are numerous and the family spans three generations. There are three young children under or around the age of ten. There’s Tom Joad, who is the central figure of the story, there’re his brother and his sister. Tom’s parents, as well as Tom’s grandparents, make the family house complete. As they have already lost their farm, we are introduced to the Joads as they are already in the final planning stages of making their way to California. California, so it is promised on a hand-note Tom’s father has, is a country full of fruits, vegetables, wine and plenty of great farm-land where work is plentiful and the Joads hope to make a new life in the West.

They sell whatever they can, buy an old jalopy to get them from Oklahoma to California. They strap and tie as much of their belongings to the car as they can and also offer the local priest to come with them. The priest is no longer a priest, albeit the Joads still think of him as a man of God. He seems a good man, a smart and just fella that later in the book becomes important.

The book follows the Joads for every other chapter in the book. Every chapter, so it seems, is intersected with a brief narration of what happened in the US at the time. It tells of the many struggles of people that fled their homes due to economic catastrophes, how they made their way by the hundreds and thousands to the West, crossing the desert in old cars, with their whole families and what awaited them when they finally got to California.

The book gives provides a fascinating and believable story of the Joads, but it is the context the small intersected chapters provides that really make this such a moving book.

It may well be timeless, but I felt that it is incredibly relevant in today’s world. Today we have masses of economic migration happening all over the world and, if it’s to be believed, it’s only going to get worse. And in this time, it becomes so vital that we take learnings from the past.

In the 1930s it was American migrants, people from Oklahoma, Kansas or Arkansas that uprooted their lives to seek new opportunities in the West, in California. They were ostracised, called names, degraded of their humanity, spat on by the local residents and abused as workers. Today it’s people from elsewhere in the world. Steinbeck’s criticism is strong and applies very well to today’s resurgance in nationalism. The same sneers and insults, the same language is applied to degrade people of their humanity.

But Steinbeck’s criticism also extends to capitalism and how it’s used the abundance of workers to the farm and factory owners’ advantage. How wealthy people with land or industry can dominate those that have nothing and are in need of food. He describes the hungry children and the desperation that is felt by all of those that came in search for a better life.

There is a brief period in the book in which the Joads almost make it, where they can almost stay and live. Otherwise, it seems, their situation is getting worse and worse. They are good people and reading their story, they grow on you. So, as a reader, you are naturally upset by the drama and disaster that befalls the family.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

The next book I read was On The Road, by Jack Kerouac. I will follow up with that summary shortly.